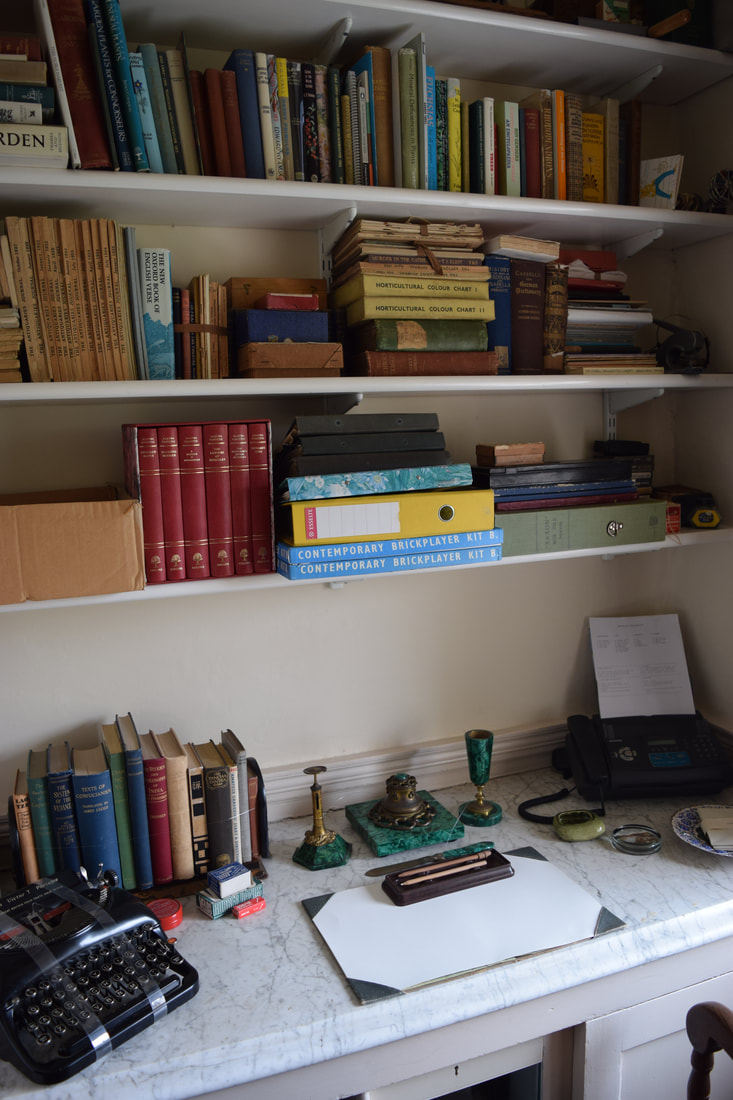

I love going to writer’s homes. Standing in the very place they wrote and trying to absorb some of their thoughts and talents. Thomas Hardy has been a particular favourite (Have a read of my blog about his Dorset life) but I’ve been saving Greenway, Agatha Christie’s home for a while. Last summer, it was on the agenda for the last day of a two-week holiday to the West Country. I’d saved it to the very last moment for the day we returned to London knowing that we’d have a wonderful last day of the holiday and I might not feel so bad about returning to the smog of West London living. Greenway is nestled in a wooded valley which runs down to the River Dart. From the lawn outside the house you have wonderful, far reaching views across the valley to the river and the house couldn’t be more perfect as a holiday home for this notorious writer.

I love playing the piano and I love an opportunity to play someone else’s piano. Not every National Trust house will let you as many are so old and delicate that it would damage them, but to my absolute delight I was allowed. I have been very fortunate recently to play a number of pianos in heritage properties and each one is different and each one fills me with delight. I recently also played in Jane Austen's house and at the National Trusts Basildon Park. I slowly sat down and played some Bach and Tchaikovsky. What an absolute treat and something I will never forget. How incredible to sit at the very same piano that Agatha Christie did and hear the same echoes of music around the walls as her and her family would have enjoyed. She loved music and one can imagine the musical entertainment that must have happened here during parties and Christmases with the family.

The smell of damp woodland was glorious after that mornings rain and William was in his element as a four year old with woods, mud and sticks to find! We had a lovely walk down the valley through the woods. And although it is predominantly trees, there are some wonderful flowers which suddenly leap out at you, providing a splash of colour amongst the greenery. The boathouse at the bottom of the valley is famous as it is the setting for Dead Man’s Folly, in which the house also features. I’m currently making my way through the audio CD read by David Suchet on my way to work in the mornings which I bought in the shop. Walking up another path, back up the valley you head to the more formal gardens at the top, and you find The Walled Gardens. There is a peach house which has been completely renovated, a vinery, vegetable plots and an allotment which is looked after by Galmpton Primary School. In the south walled gardens there are beautiful borders filled with hydrangeas which flower throughout the summer. There are also beautiful borders filled with one of my favourites, Dahlias.A great secret little discovery was the recently restored fernery, which you can find behind the walled gardens and close to the dahlia borders. The damp smell of ferns and mosses with a water fountain creates a wonderful place of tranquillity and harmony. A great place for children to play hide and seek and as I stood listening to the splash of water in the fountain, while William laughed at his reflection I was transported back to a time when life was so much calmer and the pace of everyday life slower.  After our big walk around the estate we went to the shop and the cafe for a well earned lunch. As usual with National trust cafes they have a good selection of hot and cold food, some lovely baked potatoes and a good selection of cakes and afternoon teas. The shop was stocked with a good array of national Trust products as well as plenty of books and things to satisfy every Agatha Christie fan! This was a truly magical trip and I am so glad that I have finally managed to visit. I loved it – I fell in love with it as soon as I saw it. I have been so intrigued by Agatha Christie and her life for so long, that it was really special to finally step into her shoes just for a brief moment in time. Greenway is tucked away and be warned if you intend on driving there, then you will need to book your parking space in advance. Parking spaces are timed so you only have a limited time at the property. I completely understand this is needed as parking is limited and they want to allow as many people as possible to visit. It’s just a shame as we had no option but to drive and we didn’t get to see everything as we just ran out of time. It also meant we were literally throwing jam scones down ourselves to make sure we got back to the car in time! Better planning needed next time. But you can get a bus there or the ferry over from the village of Dittisham using the Greenway Quay services. These options would allow you loads of time to explore and soak up the woodland walks and have more time to just potter around. National Trust Website

www.nationaltrust.org.uk/greenway Parking: All Parking spaces must be booked in advance of visit. You can book by visiting: http://www.nter.org.uk/ or calling 01803 842382. Same day booking is possible by telephone depending on how busy they are and phone lines open 9am-4pm. When you arrive you are greeted by a car park attendant who shows you where to go. Parking charges for non-National Trust members: £3 session.

19 Comments

I have always loved the stories, ever since my mum read the Tale of Mrs Tiggywinkle to me as a child. Many children and adults will be familiar with Peter Rabbit and his escapades in Mr McGregor’s garden, and perhaps not so familiar with Tales such as The Tale of Pie and the Patty-Pan. Perhaps even less familiar are we that many of the illustrations represent not only Beatrix Potter’s love of gardens and indeed her own garden at Hill Top, near Hawkshead in Cumbria but also of the village of Near Sawrey where she lived.

For many years the family holidayed at Dalguise in Scotland, but when this was no longer available they turned their attention to the Lake District. Close to Scotland and with similar breath-taking landscapes and water, it was here that the shy Beatrix Potter’s heart found happiness. For the rest of her life, Potter became a prominent figure in the Lake District, not only as a writer and illustrator, but as a gardener, landowner, sheep breeder, agriculturalist and wife. She described in later years London as her ‘unloved birthplace’ and both her and her brother Bertram found solace in the fresh air, surrounded by beautiful landscapes. Hill Top in near Sawrey, just to the West of Windermere was purchased with the money she had received in royalties from her early books, published by Fredrick Warne. After the untimely death of her fiancée, Frederick Warne, she bought Hill Top within two months and set about transforming it into the home and garden she had dreamed of for so long. Hill Top was and still is a warm and cosy 17th century cottage, which is part of a larger estate and far, set in some 30 acres.

She surrounded herself with colour and beauty and many of the nooks and crannies of her garden as well as the village can be seen in her books: Her vegetable patch became Mr McGregor’s Garden and Jemima Puddleducks hiding place for her eggs, her front door with its foxgloves and roses and the long front path with its deep borders and trellis work was featured in The Tale of Tom Kitten. Yet, increasingly she threw herself into life as a countrywoman, breeding a fine stock of Herwick Sheep, showing at Agricultural shows, buying farms and large areas of Lakeland to ensure its survival and preservation away from modern developments. Her friendship with Hardwicke Rawnsley, one of the founding members of The National Trust was also key in ensuring the preservation of so many thousands of acres of land.

She later said that this was how she wished to be remembered – as a countrywoman and wife. It seems that these were, in the end, more important to her than her writing and illustrating. Beatrix Potter died on 22 December 1943, following bronchitis. There were to be no flowers or mourning and her ashes were scattered above Hill Top. At her death she owned 15 farms, several cottages and around 4000 acres of land which went to the National Trust. Standing on the hillsides surrounding Hill Top, looking over to Windermere it is easy to see why Beatrix fell in love with the Lakes. I’ve always felt much abler to write and read when in the countryside, there is something incredibly therapeutic and humbling about being surrounded by such vast swathes of countryside, mountains and water. For me, I always feel like I’ve been transported into another world when I turn off the M6, and even to another era. Standing in the garden of Hill Top, it's almost hard not to expect her to appear from the cottage as you hear the crackle of the range and the old Grandfather clock chime twelve. For The Adventure

Hill Top is owned by the National Trust and open to the public. Situated in the village of Near Sawrey near Hawskshead. There is a small car park in the village (which used to be Potter’s orchard) with a short walk to the cottage. It is suitable for families, but take note that entry is by timed ticket and the cottage is small, so it’s worth getting there early. The garden is at its best in late Spring and Summer. The small village also has many places of note which are also featured in Beatrix Potter’s Books such as Buckle Yeat and the Tower Bank Arms, as well as Castle Cottage which can been seen from Hill Top across the field opposite. http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/hill-top Nearby Wray Castle is where she spent some summer holidays with her family and can be visited on the same day as Hill Top given enough time. http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/wray-castle

Stott Park is now the only surviving example of a working bobbin mill. The Lake District was a perfect area for bobbins mills which fed the busy industrial cotton mills in Lancashire, which the area was then part of. The area suited the mills perfectly with a good source of power from the many streams and a constant supply of wood from coppiced woodland. The mill was given to English Heritage in the early 1970’s by the owners who had the foresight to see that not only was the mil not sustainable any longer but also that it should be preserved for future generations as a mark of Lakeland history. To fully see the mill you need to go on one of their guided tours which takes you around the main mill building. These run every hour from 10.30am. The two ladies who showed our group around were so knowledgeable and brilliant at explaining the history, answering questions and importantly showing us how the machines worked. Ahead of my arrival I didn’t know about the tours, I probably should have read my English Heritage members guide more carefully but I timed it well so we arrived just as it was starting. It took about 45 minutes to go around the main mill building and see each section on both floors as well see how three different original machines worked.

John Harrison who was part of an established local family advertised for a tenant to take on the recently constructed mill building in 1835. It remained in the family until around 1867, being let to varying tenant bobbin masters, who ran the mill as successful businesses. The Coward family, another local family from Skeltwith Bridge who, since the 1850’s, had already gained two other bobbin mills, took on the mill and continued to run it until it finally closed in 1971. The mill was built in 1835, and has lots of windows on the first floor to allow as much light as possible for those working. During the 1870’s and 1880’s when Coward family had taken it over, the mill had several extensions and additions. The new ground floor lathe shop and the steam engine were the main elements of this modernisation of the mill. Stott Park was a mechanised mill where coppice poles were turned into finished bobbins and sent to the textiles industries throughout the world. I knew nothing of bobbin making before my trip and thanks to the fantastic guides I came away knowing so much! Several processes are involved in making a bobbin, and each man had his own job. many of the men working in the mill would have kept the same job for the time they worked there – some still working the job after 30 years! The first room had cobbled floors and as you enter the main building the floor is strewn with wood shavings, sawdust and every corner is filled with machines, tools, baskets of bobbins, swill baskets, piles of wood. It already seems like a busy working mill, but now imagine that at one time the mill would have had around 250 men and boys working there (and in its history one woman) and you start to imagine how cramped the working conditions must have been and how busy even this fairly small mill would have been on a daily basis.  On the ground floor, you first come to the circular saws when the wood is chopped into the size pieces to make the bobbins. Also here is the blocking machine which came in later in the 19th century and also chopped the wood into smaller blocks. The engine room still houses the original steam power engine built between 1870 and 1880. At the rear of the building is the New Lathe Shop which was built in the 1870’s and allowed for more space and more machinery to increase production, it was the last major improvement to the original mill. Here there are several machines such as the hand boring machine which created the central hole in the lumps of wood. The rough lathe which turned the blocks into the rough size and shape of the bobbin. One of the guides demonstrated this and made several bobbins which she then took to the next stage which involved smoothing them and creating the finished shape and size on the finishing lathe.

The mill made bobbins of all shapes and sizes, and in one of the upstairs rooms there are many many bobbins on display showing the different shapes and sizes that were used in the textiles industry. The larger ones tended not to be made from one piece, but instead were made from several pieces joined together. As the years progressed and the demand for bobbins changed due to the use of plastic and metal, the mill expanded into making other products such as yoyo’s and spindles.

Child labour during the Victorian period was rife and the mill employed a number of children to do varying jobs. Some of the boys came from the local workhouse and some as young as 8 were employed until the Factory and Workshop Act of 1878. After this Act, boys of 10 were the youngest that could, in theory, work in any factory. There were jobs that the boys were mainly given to do such as putting on glue, sorting the bobbins, climbing into the rafters to fix machinery and oil the belts, carrying away sawn pieces of wood, boring holes in the wood and cleaning them out. The guide book tells of stories where children had accidents due to working with the machinery as well as the story of a boy who was sent on an errand across the fells in winter and never returned, dying from hypothermia. Outside, spend some time in the remaining barn which has a lot of information on the history of the mill. The drying barn is worth a look as is the old blacksmiths which was in a separate building to reduce the risk of fire with all the dry wood and sawdust flying everywhere in the main mill building.

I really do recommend taking a visit here and finding out about it for yourself. Around an hour is all you need for the tour and a walk around the barn and outside and so couple easily be combined with other adventures on your day out. We went onto to have a nice walk at Tarn Hows and then finish the day with a visit to Hawskhead and dinner there before heading home just as the sun was setting around 6.30pm.

Visiting The mill is now closed until the end of March but then reopens for the Spring and Summer season. Visit the English Heritage website for further details. http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/stott-park-bobbin-mill/ Finsthwaite, Ulverston, Cumbria, LA12 8AX  The Industrial Revolution, James Lowe and Henrietta Vansittart When you think of the Industrial Revolution what images do you conjure up? For me its the hardship and bleakness of smoke infested towns, enormous brick buildings pumping, whirring, grinding and shunting - coal, tin, wool, cotton, iron and steam. But it’s not only the bleakness of the places, it's also the bleakness of the people - lined, weary faces of those trying to many a penny to survive, fresh faced excitement of those arriving from the countryside, and aristocratic men, in crisp, starched shirts and waistcoats inventing and creating new and even more fabulous inventions. Henrietta Vansittart was revolutionary in that she was one of the only great female engineers of the Industrial Revolution. James Lowe was one such inventor. Lowe had worked as a mechanist and smoke jack maker and invented a screw propeller for ships. On 23 March 1838, he took out a patent for a new screw propeller which ensured his place in history. New inventions were taken to the Royal Navy weekly, and at this time there was very little money to be made from such things. But Lowe would not give up and he spent all his wife's money on his experiments and a succession of patents reducing the family to complete poverty by the early 1850's. Therefore, it might seem strange, that his daughter, Henrietta Vansittart (nee Lowe) excelled herself to become a respected engineer and inventor in her own right, at a time when Victorian women should have been doing anything but science. Henrietta Vansittart Nee Lowe Henrietta was born in 1833, to James and Marie Lowe (nee Barnes) - she did not have the most fortunate of circumstances, she was the third daughter of six sisters and two brothers, and her father had almost bankrupted the family by 1852 through his desire to invent. However, Henrietta it seems was a social climber and had dreams of grandeur, and by 1855 she had married a lieutenant in the 14th Dragoons, Frederick Vansittart who had been based in Paris. Soon after they bought a house in Clarges Street, London and it seems he sold his commission to they could set up home. But, this was not good enough for Henrietta and in 1859 she started an affair, which lasted 12 years with the novelist and politician, Edward Bulwer Lytton. Lytton was a man of high social status and Henrietta clearly had an effect on him, although perhaps not to Disrealis liking and is said to have blamed Lyttons absences from the House of Commons on his association with Henrietta. Lytton became ill and in 1873 died, leaving Henrietta £1200 in his will and very oddly her husband, £300. She returned to her husband and lived in Twickenham. Henrietta was clearly a highly charismatic and feisty young lady who knew what she wanted and did not allow things to stand in her way. (Image 1 - see source During this time, Henrietta took a keen interest in her father’s work and accompanied him on the HMS Bullfinch in 1857 to test out the new screw propeller. She had her own ideas for how it could be developed, and after her father was tragically killed by a cart crossing the road in London in 1866, she took on her father’s work without any formal scientific or engineering training. Within 2 years she had patented another propeller to allow ships to move faster and smoother and use less fuel. In 1868, the Vansittart Propeller was patented and was used on HMS Druid - she won numerous awards for this, had articles written on her in the Times Newspaper and attended exhibitions all over the world. She was clearly a remarkable woman. It is believed that she was the only lady who ever wrote, read and illustrated with her own drawings and diagrams a scientific paper before members of the Scientific Institution. Henrietta and Twickenham Of course, no street or person would be complete without some intrigue, mystery and scandal and Henrietta certainly had some interesting moments. It is one of my favourite things about researching a house history – the stories of the people who lived there. The little scraps that give us a glimpse into the past – of squabbles and stand offs, intrigue and intellect, parties and politicians. Montpelier Row has certainly had its fair show of arguments, Henrietta seems to have lived a colourful life in all areas. It is perhaps strange that she left her husband to have her affair with Lytton in this age, and that Lytton then left both Henrietta and Frederick money in his will, £1200 to her and £300 to him, no small sum in 1873. Stranger still perhaps that she then went back to her husband. Happily or not, who knows. They appear to have become property owners, owning a number of houses in Montpelier Row Twickenham as well as on Maids of Honor by Richmond Green. These were, and still are desirable addresses. The 1871 census lists them at 4 Maids of Honor Row although records suggest she was there in 1869 without her husband. Perhaps she had bought it with funds from her patent or from Lytton. Henry George Bohn in a letter to the Richmond Twickenham Times in 1879 states that she arrived in Twickenham around 1874. In a later letter by Bohn he talks about 4 houses that she had purchased and which had then been converted into two, these appear to have been Number 4 and 5 which later became Seymour House and 1 and 2, which were known as Bell House and St Maur’s Priory. It seems by 1880 she had No 1, St Maur’s Priory (Which had been named by her) and 2, Bell House left in her possession as she had sold the others off. The 1881 census, shows that Frederick and Henrietta were living at No 1 Montpelier Row whose main frontage was on the Richmond Road. In 1878, Bell House, Number 2 was offered for lease for the sum of £100 and Seymour House, Number 3 was also offered for sale for £73,10s. Both properties were owned by Henrietta at this time and were offered for sale by Mr Fowler on 25 June 1878. It appears that a neighbour, Henry George Bohn, the infamous fine art dealer, publisher and book collector, with whom there seems to have been some rivalry and dispute purchased Seymour House from Henrietta in 1879, paying £1100.00 – a vast increase on the alleged two hundred pounds she had spent only a few years earlier. Henry George Bohn was the Vansittarts neighbour, living at North End House, just the other side of the Richmond Road. There appears to have been a great deal of rivalry amongst the two households, not least perhaps because of Henrietta’s desire to own and lease property – the same property that Bohn also wanted to own and lease. There was some argument with the local council in 1879, as the row had been changed to Montpelier Row to which Bohn took great displeasure and wrote to the Richmond Twickenham Times.(5) He had erected a sign on the from of the wrought iron railings of No 1, Henrietta’s house which stated Montpelier Row, He claims this had been agreed with Henrietta and that they had been on speaking on terms about it. However, to his annoyance, early one morning he had spied from his house, Mr Vansittart at the top of a ladder, painting the sign out! I can quite imagine the surprise and intrigue of curtains twitching as the early morning sun rose in Twickenham, to reveal an ageing Mr Vanisttart balanced among the top of a ladder, with an incensed wife in her long skirts, swishing in the dust at the bottom issuing her instructions. Bohn took to paper soon after, seemingly to air his grievances about Henrietta in public – entitle ‘The Montpelier Row Difficult’, he writes that: ‘It is with great regret that I find myself brought once more into a verbal conflict with Mrs Vansittart, but she is inexorable, and by way of publicly introducing, what appear to me to be mere figment of the brain, contrives to make me the scapegoat. I have no choice, therefore, but to reply to her, and bring out what may well be called the facts of a Tweedledum affair’ (6) It seems that Henrietta had claimed that she had thousands of pounds on improving the row, both the buildings she had purchased but also the area of land opposite, which Bohn claims that he had in fact sectioned off and made good to stop costermongers and other nuisances taking over. She stresses that she has done so much more for the neighbourhood than Bohn has ever done – keeping up with the Jones of the Victorian age. He also airs in public his annoyance at her private affairs about the purchase and sale of her properties, and mortgages she had taken out. Indeed, what obviously had been private discussions seems to have reached a head in 1879/1880 as both wrote backwards and forwards to the paper airing their grievances of one another’s behaviour over several years. A very public affair! Sadly Henrietta met a very unhappy end. In the autumn if 1883, it seems she was attending the North East Coat Exhibition of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineer at Tynemouth. She was, found wandering the streets in a very confused state of mind and was consequently committed o the Tyne City Lunatic Asylum, where she died early in 1883 on anthrax and mania. A sad end to an eventful life. One wonders why she was not moved back down South, had she fallen out with her husband again? Had she of lived one wonders what she would have gone on to achieve as a great woman engineer. SOURCES

1.Epsom and Ewell History Explorer, James Lowe and his daughter Mrs Henrietta Vansittart, http://www.epsomandewellhistoryexplorer.org.uk/Lowe.html, first accessed 15/2/2017 2.Howes, A, Capitalism's Cradle - An Economic History Blog, http://antonhowes.tumblr.com/post/115859870959/female-inventors-of-the-industrial-revolution-part 3.Intriguing History, Henrietta Vansittart Enginner, http://www.intriguing-history.com/henrietta-vansittart-engineer/, first accessed 10/2/2017 4.Wikipedia, James Lowe, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Lowe_(inventor), first accessed 10/2/2017 5. Richmond Local Studies Library, Richmond Twickenham Times, extract from a letter written to the paper from Henry George Bohn, dated 1 July 1879. 6. Richmond local Studies Library, Richmond Twickenham Times, extract from a letter written to the paper from Henry George Bohn, entitled The Montpelier Row Difficulty. 7. Photographs taken from my own personal archive, copyright Emma Louise Tinniswood 2017. |

Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed