I have always loved the stories, ever since my mum read the Tale of Mrs Tiggywinkle to me as a child. Many children and adults will be familiar with Peter Rabbit and his escapades in Mr McGregor’s garden, and perhaps not so familiar with Tales such as The Tale of Pie and the Patty-Pan. Perhaps even less familiar are we that many of the illustrations represent not only Beatrix Potter’s love of gardens and indeed her own garden at Hill Top, near Hawkshead in Cumbria but also of the village of Near Sawrey where she lived.

For many years the family holidayed at Dalguise in Scotland, but when this was no longer available they turned their attention to the Lake District. Close to Scotland and with similar breath-taking landscapes and water, it was here that the shy Beatrix Potter’s heart found happiness. For the rest of her life, Potter became a prominent figure in the Lake District, not only as a writer and illustrator, but as a gardener, landowner, sheep breeder, agriculturalist and wife. She described in later years London as her ‘unloved birthplace’ and both her and her brother Bertram found solace in the fresh air, surrounded by beautiful landscapes. Hill Top in near Sawrey, just to the West of Windermere was purchased with the money she had received in royalties from her early books, published by Fredrick Warne. After the untimely death of her fiancée, Frederick Warne, she bought Hill Top within two months and set about transforming it into the home and garden she had dreamed of for so long. Hill Top was and still is a warm and cosy 17th century cottage, which is part of a larger estate and far, set in some 30 acres.

She surrounded herself with colour and beauty and many of the nooks and crannies of her garden as well as the village can be seen in her books: Her vegetable patch became Mr McGregor’s Garden and Jemima Puddleducks hiding place for her eggs, her front door with its foxgloves and roses and the long front path with its deep borders and trellis work was featured in The Tale of Tom Kitten. Yet, increasingly she threw herself into life as a countrywoman, breeding a fine stock of Herwick Sheep, showing at Agricultural shows, buying farms and large areas of Lakeland to ensure its survival and preservation away from modern developments. Her friendship with Hardwicke Rawnsley, one of the founding members of The National Trust was also key in ensuring the preservation of so many thousands of acres of land.

She later said that this was how she wished to be remembered – as a countrywoman and wife. It seems that these were, in the end, more important to her than her writing and illustrating. Beatrix Potter died on 22 December 1943, following bronchitis. There were to be no flowers or mourning and her ashes were scattered above Hill Top. At her death she owned 15 farms, several cottages and around 4000 acres of land which went to the National Trust. Standing on the hillsides surrounding Hill Top, looking over to Windermere it is easy to see why Beatrix fell in love with the Lakes. I’ve always felt much abler to write and read when in the countryside, there is something incredibly therapeutic and humbling about being surrounded by such vast swathes of countryside, mountains and water. For me, I always feel like I’ve been transported into another world when I turn off the M6, and even to another era. Standing in the garden of Hill Top, it's almost hard not to expect her to appear from the cottage as you hear the crackle of the range and the old Grandfather clock chime twelve. For The Adventure

Hill Top is owned by the National Trust and open to the public. Situated in the village of Near Sawrey near Hawskshead. There is a small car park in the village (which used to be Potter’s orchard) with a short walk to the cottage. It is suitable for families, but take note that entry is by timed ticket and the cottage is small, so it’s worth getting there early. The garden is at its best in late Spring and Summer. The small village also has many places of note which are also featured in Beatrix Potter’s Books such as Buckle Yeat and the Tower Bank Arms, as well as Castle Cottage which can been seen from Hill Top across the field opposite. http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/hill-top Nearby Wray Castle is where she spent some summer holidays with her family and can be visited on the same day as Hill Top given enough time. http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/wray-castle

1 Comment

Stott Park is now the only surviving example of a working bobbin mill. The Lake District was a perfect area for bobbins mills which fed the busy industrial cotton mills in Lancashire, which the area was then part of. The area suited the mills perfectly with a good source of power from the many streams and a constant supply of wood from coppiced woodland. The mill was given to English Heritage in the early 1970’s by the owners who had the foresight to see that not only was the mil not sustainable any longer but also that it should be preserved for future generations as a mark of Lakeland history. To fully see the mill you need to go on one of their guided tours which takes you around the main mill building. These run every hour from 10.30am. The two ladies who showed our group around were so knowledgeable and brilliant at explaining the history, answering questions and importantly showing us how the machines worked. Ahead of my arrival I didn’t know about the tours, I probably should have read my English Heritage members guide more carefully but I timed it well so we arrived just as it was starting. It took about 45 minutes to go around the main mill building and see each section on both floors as well see how three different original machines worked.

John Harrison who was part of an established local family advertised for a tenant to take on the recently constructed mill building in 1835. It remained in the family until around 1867, being let to varying tenant bobbin masters, who ran the mill as successful businesses. The Coward family, another local family from Skeltwith Bridge who, since the 1850’s, had already gained two other bobbin mills, took on the mill and continued to run it until it finally closed in 1971. The mill was built in 1835, and has lots of windows on the first floor to allow as much light as possible for those working. During the 1870’s and 1880’s when Coward family had taken it over, the mill had several extensions and additions. The new ground floor lathe shop and the steam engine were the main elements of this modernisation of the mill. Stott Park was a mechanised mill where coppice poles were turned into finished bobbins and sent to the textiles industries throughout the world. I knew nothing of bobbin making before my trip and thanks to the fantastic guides I came away knowing so much! Several processes are involved in making a bobbin, and each man had his own job. many of the men working in the mill would have kept the same job for the time they worked there – some still working the job after 30 years! The first room had cobbled floors and as you enter the main building the floor is strewn with wood shavings, sawdust and every corner is filled with machines, tools, baskets of bobbins, swill baskets, piles of wood. It already seems like a busy working mill, but now imagine that at one time the mill would have had around 250 men and boys working there (and in its history one woman) and you start to imagine how cramped the working conditions must have been and how busy even this fairly small mill would have been on a daily basis.  On the ground floor, you first come to the circular saws when the wood is chopped into the size pieces to make the bobbins. Also here is the blocking machine which came in later in the 19th century and also chopped the wood into smaller blocks. The engine room still houses the original steam power engine built between 1870 and 1880. At the rear of the building is the New Lathe Shop which was built in the 1870’s and allowed for more space and more machinery to increase production, it was the last major improvement to the original mill. Here there are several machines such as the hand boring machine which created the central hole in the lumps of wood. The rough lathe which turned the blocks into the rough size and shape of the bobbin. One of the guides demonstrated this and made several bobbins which she then took to the next stage which involved smoothing them and creating the finished shape and size on the finishing lathe.

The mill made bobbins of all shapes and sizes, and in one of the upstairs rooms there are many many bobbins on display showing the different shapes and sizes that were used in the textiles industry. The larger ones tended not to be made from one piece, but instead were made from several pieces joined together. As the years progressed and the demand for bobbins changed due to the use of plastic and metal, the mill expanded into making other products such as yoyo’s and spindles.

Child labour during the Victorian period was rife and the mill employed a number of children to do varying jobs. Some of the boys came from the local workhouse and some as young as 8 were employed until the Factory and Workshop Act of 1878. After this Act, boys of 10 were the youngest that could, in theory, work in any factory. There were jobs that the boys were mainly given to do such as putting on glue, sorting the bobbins, climbing into the rafters to fix machinery and oil the belts, carrying away sawn pieces of wood, boring holes in the wood and cleaning them out. The guide book tells of stories where children had accidents due to working with the machinery as well as the story of a boy who was sent on an errand across the fells in winter and never returned, dying from hypothermia. Outside, spend some time in the remaining barn which has a lot of information on the history of the mill. The drying barn is worth a look as is the old blacksmiths which was in a separate building to reduce the risk of fire with all the dry wood and sawdust flying everywhere in the main mill building.

I really do recommend taking a visit here and finding out about it for yourself. Around an hour is all you need for the tour and a walk around the barn and outside and so couple easily be combined with other adventures on your day out. We went onto to have a nice walk at Tarn Hows and then finish the day with a visit to Hawskhead and dinner there before heading home just as the sun was setting around 6.30pm.

Visiting The mill is now closed until the end of March but then reopens for the Spring and Summer season. Visit the English Heritage website for further details. http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/stott-park-bobbin-mill/ Finsthwaite, Ulverston, Cumbria, LA12 8AX Following the Great Fire of London, people became increasingly aware of protecting themselves against disaster and finding ways to plan ahead to ensure the large-scale destruction of London didn’t happen in such a way again. New laws were passed to ensure the future of the metropolis and also to help move an ever-growing city forward into a new generation. New policies which were passed were concerned with rebuilding, the style of houses, design, construction and layout of the streets but also provision was made in terms of fire fighting for the city. One new law stated that each quarter of the new city should have 800 leather buckets and 50 ladders available in case of fire.[1] Each house also had to have buckets available as well. In 1667, a notable writer, doctor and economist, Dr Barbon, was heavily involved in the reconstruction of London and also in developing the first formal insurance company. It was called The Insurance Office and was based near the Royal Exchange.[2] Other companies were soon formed such as the Friendly Society and the Hand In Hand Company and every company would have its own firefighting team in order to help protect the properties they insured. The oldest documented fire insurance company was The Sun Fire insurance company founded around 1710. They still existand after many permutations are now known as the Royal & Sun Alliance In the event of a fire, all brigades from the individual insurance companies would rush to the fire in case it was one of their buildings. If the fire wasn’t in one of their properties then they would either leave or stand and watch. However, for a fee other companies would put out the fire of a someone who had a different insurance policy and eventually they would also put out fires of non-subscribers as the fire could spread easily to one of their properties on their own insurance policy. However, this was not a practical situation. There needed to be a quicker way for companies to know the buildings they represented. Firemarks were created and issued to all policyholders. Originally they were made out of tin and would be fixed to the outer wall of the house or under the eaves. As they evolved they were also made of iron, lead and brass and bore the symbol of the insurance company and often a serial number as well.  The fire marks were used during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries until there the municipal fire brigades were established. The first company to use the fire mark was The Sun Fire Office and their plaques featured the sun with a face on it. The Sun Fire Office fire marks can be seen in Montpelier Row still on several of the properties. By 1825 fire marks were no longer routinely used, many homes left up the marks regardless of whether they subscribed or not and this can be seen in Montpelier Row, Twickenham where several have remained and can still be seen clearly today. A number of properties still retain their original fire marks which were placed on the front wall, near the eaves or in the centre of the front wall. On one of the properties we can see the marks of both the Hand In Hand Insurance Company and the Westminster Insurance Companies.

The insurance companies kept very basic details of their policyholders which outlined the property, the items insured and the sums insured for. Surviving records tell us something about the residents and their status and wealth as well as the value of the house at the time. The Sun Fire records are held at the London Metropolitan Archives and these provide an sight into the lives of those whose properties were insured as well as their status and wealth. The homes in Montpelier Row were clearly for the affluent and many of those who lived there at varying stages in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were annuitants, as well as military men, lawyers and merchants.

'Susannah Course no 15 Montpelier Row Twickenham in Middlesex made on her dwelling on her dwelling house, brick and tile situate as aforesaid not exceeding five hundred and ten pounds'[6] It goes on to list the other goods and buildings which were insured and these included: Freehold goods - not exceeding £500 Painted books - not exceeding £20 Wearing apparell - not exceeding £40 Plates and cups - not exceeding £60 China and glass - not exceeding £20 Stable at the bottom of the garden - £25 Coach House - £25 The fire marks and the associated insurance records provide a wonderful little snapshot into the past. Telling us something about the people, the homes, the value of buildings and goods and that insurance policies could be taken out with such little paperwork! References

[1] https://www.irmi.com/articles/expert-commentary/the-worlds-first-insurance-company, first accessed 05/06/2017. [2] https://www.irmi.com/articles/expert-commentary/the-worlds-first-insurance-company, first accessed 05/06/2017. [3] Now number 11 Montpelier Row. The Sun Life Insurance record, London Metropolitan Archives, ADD CODE NUMBER [4] Sun life insurance, London Metropolitan Archives, ADD CODE NUMBER [5] National Archives Currency Converter from old money to new money, based on rates in 2005. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency/ [6] London Metropolitan Archives, Royal Sun Alliance insurance records, Susanna Course, 21 June 1791. Hubble Bubble Toil and Trouble For hundreds of years witches have roamed the land, disguised as elderly ladies, hiding moles and birthmarks from prying eyes, stealing animals and destroying crops. Many had black cats as their familiar, turned milk sour and spread disease. Or did they? Witch fever gripped Europe from the fifteenth to the late eighteenth century and it became a real concern to people living not only in England but across Europe. But for many elderly lonely woman, those who had been widowed or who were unwell this became a terrifying hunt of innocent people. Henry VIII passed the first witchcraft law in 1542 but it was in 1562 that it became illegal and James I of England was known for his interest in the occult. Dreadful trials and horrible persecutions took place causing much suffering and torment on largely innocent and vulnerable women. During the sixteenth century England was noted for its attempts to find and try women believed to be witches and by the mid seventeenth century a man called Matthew Hopkins became known as the Witchfinder General, condemning over 300 women to death in his time. He was paid handsomely, mainly hunting witches in East Anglia and in what was a strongly Puritan area, and reputedly killed 19 women on one day.

However, the letters ‘M’ and ‘V’ were used to represent the Virgin Mary as well as a shape which resembles ‘P’, although the reasons behind this are a little unclear. Many Witch Marks exist and have been identified in barns and churches across England but until autumn 2016 there had been no formal collection of data to see how these marks were used in secular properties and to what extent these marks had been used. Historic England undertook a survey and asked people to submit photos of the marks in their home and are currently analysing the results.

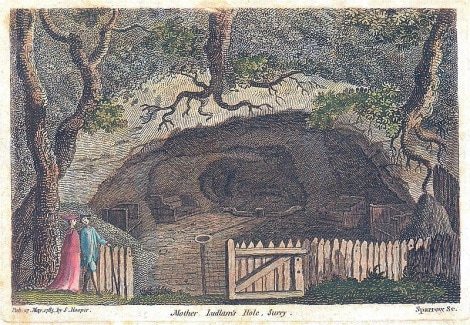

One Surrey witch who seemed to have escaped capture and became somewhat of a local legend was Mother Ludlam. There is a cave in the sandstone hills near Frensham in Surrey. Many legends surround this. But one favourite is that this was the home of Mother Ludlam, a friendly witch who provided for the local community. If villagers wanted anything then they would go to the cave and stand on a boulder outside and ask Mother Ludlam for it. When they returned home, there it was on the front door step of their homes. The only requirement was that it was returned within two days. Legend has it that one day a man requested the witches cauldron. Reluctantly as it was her property, she did grant his wish with the usual condition that it was returned in two days. However, the man failed to bring it back and Mother Ludlam left her cave in search of the man angered that he had failed to comply with the agreement. She chased him from his home and he fled apparently taking refuge in Frensham Church.

Unable to get the cauldron out, is still there to this day and has been used over the years for many things including festivals and vicars are thought to have brewed ale in it for centuries! The witch hunts reached their peak in the late sixteenth century to mid seventeenth century although the hunt did continue in some areas until much later and there are records of cases into the early nineteenth century. If you live in a pre-eighteenth century house then there’s a good chance there might be some apotropaic marks lurking somewhere. |

Archives

April 2019

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed